The following content is pulled, and updated, from a piece I assembled a few years ago. I think it is a fair companion to my previous post – Responding over Reacting. I feel it could play an important part in the arena of civil discourse – in much the same spirit as ideas in previous posts, which ultimately put some burden on each of us, personally, to engage better.

I’ll start with the framing points I used in the original content.

- The following outlines a simple concept – yet it is not common

- It suggests we have a choice in our reactions and emotions

- It outlines a sequence

- Understanding the sequence gives us a chance to do things differently

Most believe that our reactions are largely automatic, and that we have little control over most of our emotional responses, which can be represented by a simple sequence: 1) Something occurs; then 2) We feel/react in response.

Most believe that our reactions are largely automatic, and that we have little control over most of our emotional responses, which can be represented by a simple sequence: 1) Something occurs; then 2) We feel/react in response.

But I would like to suggest to you that there are more steps in the process and we have more control over our response than is commonly believed.

While certainly not a detailed scientific model, I would like to suggest 4 steps.

First – An Event Occurs. Lets say a baseball player swings and connects, driving the ball over the left field fence – a home run.

Second – You become aware of it. Lets extend our example with you witnessing it via a live broadcast on a TV at a sports bar where you are watching with some of your coworkers.

Third – You Interpret it. Now that you are aware of it, you process it. Things including your like or dislike for the team or player, how invested you are in the sport in general, if you have a bet with a friend on the game, for how much money, and more, shade your opinion of the event. In this case it is your team, and you stand to collect $20 from your friend.

Third – You Interpret it. Now that you are aware of it, you process it. Things including your like or dislike for the team or player, how invested you are in the sport in general, if you have a bet with a friend on the game, for how much money, and more, shade your opinion of the event. In this case it is your team, and you stand to collect $20 from your friend.

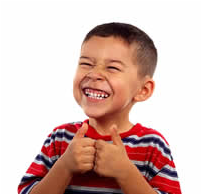

Fourth – You act/react in response. Your response flows from your intepretation. And how you feel about it too. Your glad. You and your coworkers cheer and applaud and some cash is coming your way.

Fourth – You act/react in response. Your response flows from your intepretation. And how you feel about it too. Your glad. You and your coworkers cheer and applaud and some cash is coming your way.

So far, nothing substantially different from the two-step sequence. I will expand on the significance of the distinctions shortly.

Lets change the scenario just slightly. Same baseball game, same player, same home run – the same event occurs (first step). You are in the same sports bar with the same coworkers and witness the hit in the same way. Second Step– You become aware in the same way.

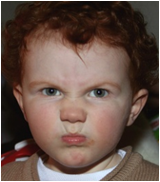

However, it is not your team – it is the opposition. That means you will lose the bet. Third Step – You’re going to have a different opinion, and then, fourth step – a different feeling flows. You are upset or angry.

However, it is not your team – it is the opposition. That means you will lose the bet. Third Step – You’re going to have a different opinion, and then, fourth step – a different feeling flows. You are upset or angry.

Steps 1 and 2 are the same. Steps 3 and 4 are different.

This demonstrates that the event (step 1) is well separated from our response (step 4).

Now, let’s suppose you don’t follow baseball, did not go out with your coworkers, and never placed a bet. You don’t watch the game at home either, because you have no interest. You know nothing of the game or home run. It never comes into your awareness. If you are not aware of it, Steps 3 & 4 never take place (for you) – no interpretation, no associated happiness or anger. This further demonstrates the separateness of the event from the other steps.

Let’s change the second scenario only slightly. Instead of experiencing the home run via TV, you find out about it, after the fact, from your neighbor, and friend, who lives in the same apartment complex, when you are collecting your mail. Let’s say your interpretation and reaction are essentially the same. And since your neighbor is a friend, you blurt out an expletive. This separates the event (step 1) further in time from the successive steps. The awareness step is similar – though not identical.

Let’s change the second scenario only slightly. Instead of experiencing the home run via TV, you find out about it, after the fact, from your neighbor, and friend, who lives in the same apartment complex, when you are collecting your mail. Let’s say your interpretation and reaction are essentially the same. And since your neighbor is a friend, you blurt out an expletive. This separates the event (step 1) further in time from the successive steps. The awareness step is similar – though not identical.

From these examples, it is reasonable to conclude that the event is not directly responsible for your reaction. We can also see that your biases and interests are the basis of your opinion and the source of your reaction – not the event itself.

Now, another small adjustment. Same as just above, except the neighbor is someone you find attractive, a romantic possibility. Instead of an expletive, you soften the descriptor(s) you use to convey how you feel about the event.

This demonstrates an important idea. You chose to handle your response differently. In fact, you paused during step 3, if only so briefly, and decided that it would be better for you to say something gentler on the matter. The trigger-event has not changed, nor the awareness.

This demonstrates an important idea. You chose to handle your response differently. In fact, you paused during step 3, if only so briefly, and decided that it would be better for you to say something gentler on the matter. The trigger-event has not changed, nor the awareness.

But, you invoked a change at step 3 – which affected what followed.

As an event seeps into our awareness (step 2) we engage our memories, biases, concerns, expectations, prior feelings, other sensations, etc. Blended together they color the formation of our perception (step 3).

Setting aside, for now, reactions to genuine threats of imminent danger driven from our reptilian brain, I submit that we have the ability to exercise more control over the shading we apply to events than we give ourselves credit for.

Here is an alternative example. Let’s say a person says something about us (step 1). And we hear it (step 2). We decide (step 3) what we think of the comment and thus how we feel about it (step 4).

To tune this, let’s say the person is a friend. We (decide to) give credence to their statement because we know them, they have some acumen in the subject area, and they know us. We color our perception accordingly and feel OK.

To tune this, let’s say the person is a friend. We (decide to) give credence to their statement because we know them, they have some acumen in the subject area, and they know us. We color our perception accordingly and feel OK.

Now let’s add a twist. Assume no difference in the words or style of delivery (step1 is the same) and we hear it in the same way (step 2).

The person is not familiar to us, or with us, and we know little of their credentials. We shade it differently (step 3) and take umbrage (step 4).

The person is not familiar to us, or with us, and we know little of their credentials. We shade it differently (step 3) and take umbrage (step 4).

We own how we feel

The actual message content (the same in both cases) is not responsible for our resultant feeling. It starts the process, but our perception, and our coloring of it, the feeling from it – we own. It is incredilbly common, in our society, to say and hear “they hurt my feelings.” And it may seem like splitting hairs to some – but that common utterance is not accurate. Being more precise – they said something, and we decided to let it bother us (or not). Because steps 3 clearly belongs to us, we consequently own how we feel about it.

An opportunity

So, all this leaves us with an opportunity. An opportunity to step-up on our own behalf. To pause and adjust at step 3. If we think back, many of us may have been taught, when we were young, to count to ten before getting angry. Good advice – because, in the intervening seconds, we can (if we try) get a hold of the thoughts stirring our (potential) anger, check them for accuracy, and also weigh the options, before getting to anger or an alternative state.

How about memories?

Again, trying to keep it simple, let’s say a memory is a combination of steps 1 & 2. It gets conjured into our awareness. We could have guided our thoughts toward remembering, or something else could have triggered the memory. For now, let’s leave it at that.

Let’s say we recall that home run six months later. Then we ponder it (step 3) and our feeling follows (step 4). We may likely have a very similar reaction to the original one. But, maybe not – time may have provided distance and perspective.

Let’s say we recall that home run six months later. Then we ponder it (step 3) and our feeling follows (step 4). We may likely have a very similar reaction to the original one. But, maybe not – time may have provided distance and perspective.

As expressed earlier, the event of six months prior does not trigger our response directly. The memory is the beginning of the process. Again the event is well separated from the reaction. We cannot truly say that the home run is responsible for how we feel now. Our recollection (step 2) then our perception (step 3) is the source of our emotion (step 4). We own how we feel about the memory too.

If we so choose, we have the ability to adjust our perception (step 3) about that past event in a broader context of other things and much that has happened since.

Perhaps not easy – but worth it

Perhaps not easy – but worth it

I’m not suggesting this is necessarily easy. Especially if we are like many — practiced in just reacting. I say practiced meaning having done it over, and over, again.

I am suggesting it is both possible and beneficial.

For many, my spelling this whole thing out comes to “duh – we knew that” or “we already do that.” To them I say “Terrific.” Like I said when I started, it is a simple concept that I think is not commonly followed. And I think showing the distinct steps is worthwhile.

For those to whom this is foreign, getting from an inability to do so, to an ability, will also take practice, repetition. With practice this can become like second nature (as we may have previously assumed automatic reactivity was).

For those to whom this is foreign, getting from an inability to do so, to an ability, will also take practice, repetition. With practice this can become like second nature (as we may have previously assumed automatic reactivity was).

I think it is worth it. First, for our own sake, and more broadly for our relationships and exchanges with others. Even if they do not choose to temper (interesting word in this context) their thoughts and response, our doing so might help keep a tense dialog from getting worse – and possibly help steer it back toward a productive end. If both parties can leverage it, imagine how much more we might advance instead of spinning in circles.

It can help in day to day living. And it can help civil discourse.